By Michael Ashcraft —

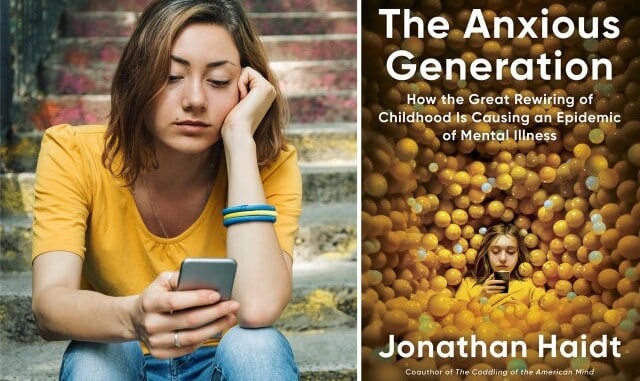

Imagine a world where childhood, that sacred realm of scraped knees and secret forts, has been quietly hijacked—not by overbearing adults or dystopian overlords, but by a glowing rectangle small enough to fit in your pocket. This is the world Jonathan Haidt unveils in The Anxious Generation: How the Great Rewiring of Childhood Is Causing an Epidemic of Mental Illness. Like a detective piecing together a sprawling mystery, Haidt traces the threads of a seismic shift in how kids grow up—a shift that began around 2010 and has left an entire generation more fragile, more isolated, and more anxious than ever before. It’s a story of tipping points, unintended consequences, and a desperate plea to reclaim what’s been lost.

Let’s start with the numbers, because they’re staggering. In the early 2010s, after a decade of relative stability, adolescent mental health in the United States (and much of the Western world) took a nosedive. Depression rates doubled. Anxiety spiked. Self-harm among teenage girls surged by 188%, and suicide rates for younger adolescents climbed—167% for girls, 91% for boys. Haidt, a social psychologist with a knack for spotting cultural currents, doesn’t see this as mere coincidence. He points to a culprit: the smartphone. Not just the device itself, but what it ushered in—a “phone-based childhood” that replaced the rough-and-tumble, play-driven world kids once inhabited.

This isn’t a nostalgic lament for the good old days, though. Haidt’s argument hinges on a fascinating duality: overprotection in the real world and underprotection in the virtual one. Picture a kid in the 1980s, pedaling a bike down a suburban street, free to roam until dusk. That child was antifragile—built to bend, not break, through skinned elbows and playground spats. Fast-forward to the 2010s, and that same kid is tethered to a screen, insulated from physical risk but plunged into a digital Wild West of infinite comparisons, curated perfection, and algorithmic rabbit holes. Haidt calls this shift “the Great Rewiring of Childhood,” and it’s as if someone flipped a switch on human development.

What’s so special about 2010? That’s when smartphones went from niche gadgets to ubiquitous appendages, thanks to the iPhone’s explosive rise and the advent of front-facing cameras. Social media platforms like Instagram and Snapchat took off, pulling kids—especially girls—into a vortex of likes, filters, and relentless self-scrutiny. Boys, meanwhile, retreated into immersive gaming worlds and, increasingly, pornography. Haidt unpacks more than a dozen mechanisms behind this rewiring: sleep deprivation from late-night scrolling, attention fragmentation from constant notifications, addiction to dopamine-driven feedback loops, and the loneliness that creeps in when virtual “friends” replace real ones. It’s a perfect storm, and Gen Z (born after 1995) was caught in its eye.

Here’s where Haidt’s tale takes a Gladwellian twist: it’s not just about technology. It’s about what technology displaced. Play—unstructured, unsupervised, gloriously messy play—had been eroding since the 1980s, thanks to helicopter parenting and a culture obsessed with safety. By the time smartphones arrived, the “play-based childhood” was already on life support. Haidt leans on developmental science to argue that kids need this chaos to thrive. Free play teaches negotiation, resilience, and emotional regulation—skills you can’t learn from a screen. Without it, children become fragile, unable to cope with setbacks or solitude. The phone didn’t create the problem; it delivered the knockout punch.

Take girls, for instance. Haidt shows how social media amplifies their relational instincts into a toxic brew of social comparison and perfectionism. A 2021 leak from Facebook (now Meta) revealed the company knew Instagram was harming teenage girls’ mental health—yet kept pushing. Boys, on the other hand, withdraw into virtual realms, trading real-world risk for digital escape. The result? A generation where connection is shallow, sleep is scarce, and anxiety is the norm.

But Haidt doesn’t stop at diagnosis. Like a storyteller circling back to hope, he offers a way out—four simple rules to undo the damage. No smartphones before high school. No social media until 16. Phone-free schools. More unsupervised play and independence. These aren’t pie-in-the-sky ideals; they’re practical fixes rooted in collective action. He imagines parents banding together to delay smartphone adoption, schools locking devices away during the day, and governments enforcing age restrictions on tech platforms. It’s a vision of childhood reborn, where kids climb trees instead of follower counts.

Is Haidt right? Critics might argue he overplays correlation as causation—after all, climate change, inequality, and global unrest also haunt Gen Z. Yet his data, from longitudinal studies to leaked corporate memos, builds a compelling case. And there’s something intuitive here, too. We’ve all seen kids hunched over screens, faces lit by blue glow, oblivious to the world beyond. We’ve felt the unease of a society trading presence for pixels.

In The Anxious Generation, Haidt isn’t just chronicling a crisis—he’s mapping a tipping point. Like the advent of the printing press or the Industrial Revolution, the smartphone era has rewired how we live. But unlike those upheavals, this one’s still in our grasp. We can pull back, reintroduce play, and let kids be kids again. It’s a story of loss, yes, but also of possibility—a reminder that the tools we wield don’t have to define us. Sometimes, the smallest shift, like putting down a phone, can change everything.

About this writer: Michael Ashcraft is the editor-in-chief of Pilgrim Dispatch.