BBC News, Essex

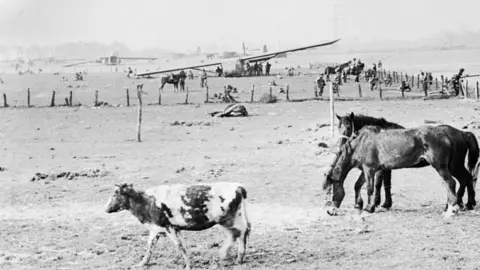

Danny Mason’s handouts

Danny Mason’s handoutsIt was a battle that ended World War II in Europe, but little is known to everyone except military history enthusiasts.

British, Canadian and American troops took off mainly from Essex Airfield on March 24, 1945, and were dropped directly above the German line on the Rhine.

The men packed empty troopers and gliders descended into intense fighting conditions, bringing rapid success, but lost a great life. About six weeks later, a victory was declared in Europe.

Chris Brock held an event at Raf Rivenhall, one of the departure airfields, and recalled the dead, saying, “It’s an immeasurable story.”

“When I saw a video of the men in Rivenhall at the final brewing, they gave a thumbs up before they went into the glider and gave them a sign of victory, and within three hours they were dead.

102-year-old Peter Davis towed a Dakota plane from Rough Woodbridge in Suffolk and carried a “segregation of a 17-pound gun, a towing vehicle and eight staff guns.”

He volunteered for the Glider Pilot Regiment in 1942. Because I thought he was more “exciting” than in his time as my manning in the Royal Artillery Anti-Air Unit Army.

“It’s like flying a brick. There’s only one way. It’s down,” said Davis, from Bollington, Cheshire.

“There was a lot of flak, we lost control and we lost a big chunk of one wing.

“When we hit the ground, and I mean hits – we were in the wrong place in a load of very angry Germans, and it was total mess.”

One American glider came down within 50m (about 160 feet).

But with co-pilot Bert Bowman, he made it across the battlefield to the intended drop zone and returned to England.

Getty Images

Getty Images“The allies landed directly on the Germans, many gliders were shot down, and many paratopers were shot in the air. Eighties, only Raf Rivenhall, lost their lives.”

Operation Varsity was the largest single aerial project in history, with over 16,000 men being dropped into West Germany on the same day.

Its purpose was to establish a bridgehead across the Rhine for the main Allied advance into Germany and to rapidly push towards Russian forces arriving from the east.

The first part was the looting of a ground attack operation “which was the largest river crossing in history and was carried out by British and Canadian forces.”

The intention was for the amphibious forces on the west side of the Rhine to join the airborne army that had been dropped east.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesVarsity took place just five months after Arnhem’s tragic battle, with 90% of the casualties in the Glider Pilot Regiment.

RAF pilots such as Brian Latham, who were sent to Texas, were among the hundreds who “volunteered” for glider services to learn to fly fighter planes.

“We were told that if we didn’t volunteer, we would never fly again, join the infantry or descend the mine,” said Latham (101) from Landudono, Conway, Wales.

However, he soon realized that being a Guilder pilot was a “command-like elite.”

“We weren’t tough, they made us tough. I became a trained infantryman,” he said.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesFlying from Rough Gosfield near Braintree in Essex, Latham carried a mortar section with a jeep and trailer, which was dropped into ground smoke and heavy anti-aircraft fire.

“We just jumped into the smoke and it was all very exciting and we landed where we should have done in Haminkologne,” he said.

“At that time, we were attacked by German tanks (crossing the Rhine) by the bridge held by the Royal Ulster Rifles until the appearance of the Second British Army.”

Eventually he returned to the UK, but was grateful that he would not return to the home station at Raf Broadwell in Oxfordshire, as “we lost so many people.”

Of the 890 Glider Pilot Regiment personnel who participated in Varsity, more than 20% were killed or injured.

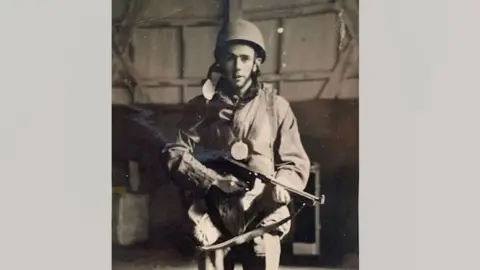

Danny Mason’s handouts

Danny Mason’s handouts“We were dropped quickly among Germans who had never been tried before, but we knew it was a suicide fall,” Danny Mason said.

“But that didn’t bother us. We were young and enthusiastic and thought, ‘We’re fine, it’s fine.’ ”

“I thought the Germans were losing and not in good fighting conditions, which was easy, but not in that case,” said Mason, who now lives in Ludlow, Shropshire, in ’98.

Ashley Mason

Ashley MasonAt least 1,070 members of the US 17th Airborne Division and the UK 6th Airborne Division, including Canadians, have been killed, and thousands more injured.

“But within four or five hours, we achieved what we were trying to do,” Mason said.

He advanced 600 miles through Germany within two weeks before being injured.

“It was the battle that ended the war, but no one was interested in it,” he said.

“I asked my old commander about it and he said it was because everyone was sick of it. It was a six-year war and when VE Day came, it was a very big relief.”

Getty Images

Getty ImagesBullock provided additional context.

“Three weeks after Varsity, the Belsen concentration camp was released. Two weeks later, Hitler committed suicide, and a week later Germany surrendered. Perhaps little has been spoken since the event overtook himself.”

Currently working as the BBC’s International Operations Security Manager, he lives near RAF Revenhall and began researching the story 10 years ago.

The 60 gliders, towed by two RAF squadrons, left the airfield at 07:00 GMT on March 24, 1945, carrying part of the 6th Airborne Division.

But some of that history is still lost.

“There is no record of which gliders and what happened to each man, or who flew, just anecdotal evidence and individual stories I could track,” he said.

He commissioned a memorial “remember all those who flew out of Riven Hall and died that day.”

It will be announced at the event on March 23rd, with military vehicles, static stands, re-establishers, presentations and fly-pustos by Dakotas.

A supplementary service ceremony will be held at 7:00 the next day.

Thank you to the Glider Pilot Regiment Association and the Parachute Regiment Association.